John Barry’s The Great Influenza: The Story of the

Deadliest Pandemic in History combines the many elements of the 1918 influenza

pandemic to provide a well written, very accessible book, even as it discusses complex topics. Barry handles the politics, the military,

the genetics, the medical, the government and psychological factors that

combined to make this epidemic so deadly.

He ties all the threads together into a coherent narrative. In the process, he illustrates how important

1918 was in forming our modern responses to pandemics

Eric Maroney, author of Religious Syncretism, The Other Zions, The Torah Sutras & published fiction

Tuesday, April 28, 2015

Friday, April 24, 2015

Thursday, April 23, 2015

Tormented Master: The Life and Spiritual Quest of Rabbi Nachman of Bratslav

Tormented Master: The Life and Spiritual Quest of Rabbi Nachman of Bratslav is Rabbi Arthur Green’s full length biography of the founder of Bratslav Chasidism, one of the most colorful and interesting personalities in the history of Judaism.

I have enjoyed all of Rabbi Green’s work on modern Jewish issues, especially Radical Judaism. He is a clear and staunch advocate of injecting modern Jewish practice with Hasidic heart and soul, without the stringency of Hasidic halakah. I consider myself a Brastlaver, although the entry requirements are not rigorous (you simply call yourself one when people ask). So, to wrap up, I should love this book unreservedly.

Yet, I do not. I have tried to read this book for several years, and put it down repeatedly. I tried once more, and finished it, except for some of the Excurses material at the end. It seems like Green turned off his obvious talent for explaining complex topics simply in this work. He gets too involved in the nitty-gritty of concepts, at the expense of the big picture. The reader, well this reader, gets lost in the maze of his prose.

And the book could have been great! Perhaps Green, in his zeal to create the first “real” biography of Rebbe Nachman, sacrificed general intelligibility for scholarship. Regardless, he left us a work with some redeeming qualities embedded in thick text that taxes the reader.

I have enjoyed all of Rabbi Green’s work on modern Jewish issues, especially Radical Judaism. He is a clear and staunch advocate of injecting modern Jewish practice with Hasidic heart and soul, without the stringency of Hasidic halakah. I consider myself a Brastlaver, although the entry requirements are not rigorous (you simply call yourself one when people ask). So, to wrap up, I should love this book unreservedly.

Yet, I do not. I have tried to read this book for several years, and put it down repeatedly. I tried once more, and finished it, except for some of the Excurses material at the end. It seems like Green turned off his obvious talent for explaining complex topics simply in this work. He gets too involved in the nitty-gritty of concepts, at the expense of the big picture. The reader, well this reader, gets lost in the maze of his prose.

And the book could have been great! Perhaps Green, in his zeal to create the first “real” biography of Rebbe Nachman, sacrificed general intelligibility for scholarship. Regardless, he left us a work with some redeeming qualities embedded in thick text that taxes the reader.

Thursday, April 16, 2015

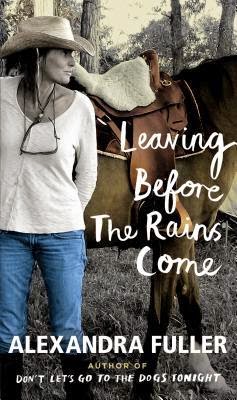

Leaving Before the Rain Comes

Having read two of Alexandra Fuller’s books before this one, Leaving Before the Rain Comes, it is not at all surprising that she would divorce her husband, and that she would write a memoir about this experience.

In a sense, the groundwork was laid in her breakout memoir, Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight. The end of that book is extremely compact, and in an interview Fuller acknowledged that the book had a longer ending. Here, apparently, is the cut material reworked to 2015.

If this is not the standard divorce narrative it is because Fuller is an exceptional writer, keenly, almost painfully honest in her approach. She spares no one and nothing her scrutiny (at least in the material she decides to show us). She uses the language powerfully, poetically, expressing ideas, emotions, and concepts, over a wide, eloquent range. She can write emotionally or analytically with equal skill. When she is close to her material, as she is in this book, her writing is simply mesmerizing.

It is when she moves beyond the topic of Africa where her prose starts to sag. Not much, but it is obvious that Africa is her inspiration. Her best work deals with two topics: Africa, and her life. And unless I have misjudged this very talented writer, you should buy and read any book where she handles both topics.

In a sense, the groundwork was laid in her breakout memoir, Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight. The end of that book is extremely compact, and in an interview Fuller acknowledged that the book had a longer ending. Here, apparently, is the cut material reworked to 2015.

If this is not the standard divorce narrative it is because Fuller is an exceptional writer, keenly, almost painfully honest in her approach. She spares no one and nothing her scrutiny (at least in the material she decides to show us). She uses the language powerfully, poetically, expressing ideas, emotions, and concepts, over a wide, eloquent range. She can write emotionally or analytically with equal skill. When she is close to her material, as she is in this book, her writing is simply mesmerizing.

It is when she moves beyond the topic of Africa where her prose starts to sag. Not much, but it is obvious that Africa is her inspiration. Her best work deals with two topics: Africa, and her life. And unless I have misjudged this very talented writer, you should buy and read any book where she handles both topics.

Monday, April 13, 2015

The Hilltop: A Novel, by Assaf Gavron

The Hilltop: A Novel, by Assaf Gavron, has been called the “Great

Israeli Novel” which I suppose means, that in a serious sense, it captures the

various currents of the current Israeli experience in novel form, in one stream. Yes, I can see that label, and in many ways

it fits. The problem is the novel is

very programmatic in its attempts to show all the sides of the Israeli

experience. The obviousness of this

reach mars the book. It is not an

organic display of people living their lives, but more a showcase. So in some ways the presentation of the characters and their situations is a bit stilted and obvious.

That said, Gavron has written a novel with many redeeming

qualities. There are at least a dozen

major characters. He brings them in and

out of the narrative with ease and agility.

Gabi, who really functions as the hero of this novel, is complex,

strange, very distasteful at certain times, but ultimately is a man how is

learning from his mistakes and getting on with the business of life. Gavron also has an excellent handle of the

baroque bureaucracies of the Israel government, and a very comic sense of

things. All this gives the novel no

little credit.

Thursday, April 9, 2015

One-Hundred Best Loved Poems

The Dover “One-Hundred Best Loved Poems” has resonances far beyond the poems on the page. If you read poems in school, reading these will bring back the words like distant, barely traceable memories. Most of these poems belong to the heritage of western culture, and even if you have not read the poem, or don’t remember reading it, you can trace the fine lines where the literary culture has borrowed, stolen or hijacked (all fairly) the words and meaning(s) of these poems.

Take Yeats’s poem The Second Coming which has such memorable and well used lines as “things fall apart,” the title of Chinua Achebe’s celebrated novel, “the centre cannot hold” used in a variety of titles and contexts, mostly about mental illness and “slouches toward Bethlehem” used by Joan Didion in her famous series of essays about the rise and fall of the 60s.

This is only one of 99 reasons to read this collection and get back in touch with some of the central poems of our tradition, and then move on to ever widening circles of poetry and its meaning.

Take Yeats’s poem The Second Coming which has such memorable and well used lines as “things fall apart,” the title of Chinua Achebe’s celebrated novel, “the centre cannot hold” used in a variety of titles and contexts, mostly about mental illness and “slouches toward Bethlehem” used by Joan Didion in her famous series of essays about the rise and fall of the 60s.

This is only one of 99 reasons to read this collection and get back in touch with some of the central poems of our tradition, and then move on to ever widening circles of poetry and its meaning.

Tuesday, April 7, 2015

The History of Garden City

The History of Garden City, New York (my hometown) by long time historian of the village, M.H. Smith, makes for border-line interesting, if not somewhat stultifying, reading. Ms. Smith is from another time (she died in 1991 at the age of 90) and it often shows in her prose and remarks.

Garden City was a planned village created by Alexander Stewart, America’s first department store tycoon, in the years following the Civil War. Stewart brought a large tract of the Hempstead Plains, the largest prairie east of the Mississippi. The common yarn told about the Hempstead Plains was that at the founding of Garden City it had become a wasteland. This simply means that after cattle pasturing and horse racing, the plains no longer had any economic use. The result is what we have today: small patches of the plain remaining (only a few acres from the original 60,000 acres) which are being preserved by dedicated volunteers. So, one era’s wasteland is another’s nature preserve. Certainly nothing new in that statement.

That is simply one example. The book is largely uncritical in its approach. This was a book written to sing praises to the Village of Garden City, not to present genuine history. Yet, it is the only full length history of the town. So in lieu of doing your own private research, this book has value.

Garden City was a planned village created by Alexander Stewart, America’s first department store tycoon, in the years following the Civil War. Stewart brought a large tract of the Hempstead Plains, the largest prairie east of the Mississippi. The common yarn told about the Hempstead Plains was that at the founding of Garden City it had become a wasteland. This simply means that after cattle pasturing and horse racing, the plains no longer had any economic use. The result is what we have today: small patches of the plain remaining (only a few acres from the original 60,000 acres) which are being preserved by dedicated volunteers. So, one era’s wasteland is another’s nature preserve. Certainly nothing new in that statement.

That is simply one example. The book is largely uncritical in its approach. This was a book written to sing praises to the Village of Garden City, not to present genuine history. Yet, it is the only full length history of the town. So in lieu of doing your own private research, this book has value.

Friday, April 3, 2015

The Lincolns: Portrait of a Marriage

The Lincolns: Portrait of a Marriage by Daniel Mark Epstein is a very well-written treatment of the Lincoln’s often stormy marriage. Epstein has become quite a proficient writer on Lincoln and all things Lincoln related. He knows his material, can write well, and provides a compelling, fleshed out portrait of Lincoln and his world.

In this book, Epstein gives the definite impression that part of the president’s well-known patience and ability to bear burdens came, in part, through his marriage to Mary Todd. They were an unlikely couple, and the opposing traits which drew them together in their early years drew them apart later. This weighed heavily on Lincoln, but in reading Epstein’s book, one can’t help but conclude that it also helped propel Lincoln to transform suffering into patience and fortitude.

If he could struggle to make a bad marriage work, he could bring the nation back together. This may seem like a stretch, but Lincoln lived his private, family life in the White House as the Civil War unfolded. Epstein shows how they were very much intertwined.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)